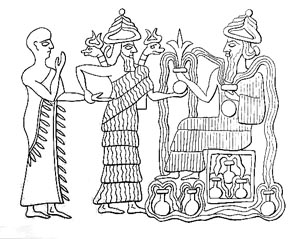

The Epic of Atrahasis on a tablet from the British Museum, London (Britain). © British Museum

The Atrahasis Epic, named after its human hero, is a story from Mesopotamia that includes both a creation and a flood account. It was composed as early as the nineteenth century B.C.E. In its cosmology, heaven is ruled by the god Anu, earth by Enlil, and the freshwater ocean by Enki. Enlil set the lesser gods to work farming the land and maintaining the irrigation canals. After forty years they refused to work any longer. Enki, also the wise counselor to the gods, proposed that humans be created to assume the work. The goddess Mami made humans by shaping clay mixed with saliva and the blood of the under-god We, who was slain for this purpose.

The human population worked and grew, but so did the noise they made. Because it disturbed Enlil’s sleep, he decided to destroy the human race. First he sent a plague, then a famine followed by a drought, and lastly a flood. Each time Enki forewarned Atrahasis, enabling him to survive the disaster. He gave Atrahasis seven days warning of the flood and told him to build a boat. Atrahasis loaded it with animals and birds and his own possessions. Though the rest of humanity perished, he survived. When the gods realized they had destroyed the labor force that had produced food for their offerings they regretted their actions. The story breaks off at this point, so we learn nothing of the boat’s landing or the later Atrahasis.

The account has similarities to the Primeval History, including the creation of humans out of clay (see Genesis 2:7), a flood, and boat-building hero. For the text of the Atrahasis Epic see Pritchard (1969: 104-106). For a detailed study see W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard, Atrahasis (Oxford: Clarendon Lambert, 1969).

Atrahasis & Human Creation

When the Gods did the work they grew weary and decided to create human beings.

This later Akkadian version of the flood story and the creation of humanity and fits between the Sumerian version and the Babylonian version in the Epic of Gilgamesh. The following excerpt is taken from Myths From Mesopotamia: Gilgamesh, The Flood, and Others, translated by Stephanie Dalley. It is related here for educational purposes only.

Read the rest

Tablet XII provides further insight into some of the major themes and questions explored in the first eleven tablets. Is there an afterlife? What is the nature of it? What earthly behaviors are rewarded there? By the conclusion of Tablet XI, Gilgamesh was forced to accept the limits of mortal existence and be satisfied with its attainable rewards. Questions about the “state of being” in death had fiercely possessed him, however, and the answers remained a mystery.

Tablet XII provides further insight into some of the major themes and questions explored in the first eleven tablets. Is there an afterlife? What is the nature of it? What earthly behaviors are rewarded there? By the conclusion of Tablet XI, Gilgamesh was forced to accept the limits of mortal existence and be satisfied with its attainable rewards. Questions about the “state of being” in death had fiercely possessed him, however, and the answers remained a mystery. The term ‘Sumerian King List’ refers to the listings of Sumerian and neighbouring ruling dynasties derived from a number of sources mainly discovered early in the last century. The principal, most comprehensive, of these is the ‘Weld-Blundell Prism’. There are some twenty copies of the list or parts of it, some of which had been discovered before the Prism (Bienkowski & Millard 2000 169); (Wikipedia). Later king lists preserved and utilised this format at least up to the ‘Babylonica’, the History of Babylon, written by Berossus during the Hellenistic period in about 280 BC. (Burstein 1989 1)

The term ‘Sumerian King List’ refers to the listings of Sumerian and neighbouring ruling dynasties derived from a number of sources mainly discovered early in the last century. The principal, most comprehensive, of these is the ‘Weld-Blundell Prism’. There are some twenty copies of the list or parts of it, some of which had been discovered before the Prism (Bienkowski & Millard 2000 169); (Wikipedia). Later king lists preserved and utilised this format at least up to the ‘Babylonica’, the History of Babylon, written by Berossus during the Hellenistic period in about 280 BC. (Burstein 1989 1)